Discovering a Borderlands Community in Arizona

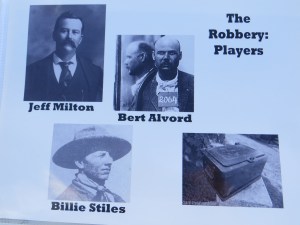

My husband and I headed to Camp Naco in southern Arizona on a Saturday morning to see where Buffalo Soldiers played baseball and learn about the outlaw Cactus League formed in 1910. Like many historic locations, the actual structure is long gone but a gifted storyteller skillfully laid out historical facts along with a few artifacts to help us to visualize the field.

After viewing the field, we got in our cars to drive to the elementary school in the small town of Naco for his formal presentation.

This was a first for me. Naco is a place I typically drive past on a visit to Bisbee. I have an awareness that a small number of people live there but that’s pretty much it. While navigating the streets to the school, I catch a glimpse of a Mexican flag on the horizon.

The Mexican flag flies over Naco, Sonora on the southern border.

The baseball presentation was very interesting, even for a person like me who isn’t particularly into the sport. It helped me understand the popularity of a game in small towns across America and Mexico during a time without radio, television or internet.

An hour later it was time to get back in my car and drive home, but I wanted a closer look at the Mexican flag I had seen earlier. I didn’t have far to travel. Less than a block away was Towner Street which leads to the Naco Port of Entry.

I live in southern Arizona. The idea that our shared border is part of the landscape is something those of us who live here are familiar with. I used to drive to Nogales, Arizona (about 45 minutes away) to walk over to Nogales, Sonora for a quick shopping trip and lunch. I haven’t done that in more than 15 years. I live in the southeastern corner of the state in Cochise County. I drive through a Border Patrol checkpoint inside the U.S. every time I head to Tucson. It’s not uncommon to see their vehicles in the streets here. Over the past five years it’s become a regular thing to see them in high speed pursuits of human smugglers through our communities. Turns out that most of these drivers are American teenagers recruited on social media with the promise of $1K per head. Some aren’t even old enough to have a drivers license and their sketchy driving while being chased by law enforcement has lead to serious accidents and even a couple of deaths.

Just up the road from my home is the Army installation I worked on for more than 25 years. It is now the headquarters for the military southern border mission bringing an additional 500 Soldiers to my community and regular helicopter traffic. That’s not really all that shocking. In retirement I’ve taken up the mission of telling the stories of Soldiers who were here more than 100+ years ago to conduct a similar mission.

The Gay 90s Bar has been wetting border visitors’ whistles since 1931. A painting of Patrick Murphy’s accidental bombing of the town adorns the front of the building.

As I got out of my vehicle to walk down Towner Street to our border with Mexico, the view in front of me wasn’t seen through a filter of drugs, human misery, cartels and violence but one of small communities co-existing. I bumped into our baseball historian who invited me into the Gay 90s Bar for a drink and presumably colorful stories. Lou waited patiently in the car while I played documentarian so I asked for a rain check. Before I continued my stroll, the historian recommended a nice restaurant on the Sonoran side of the border and shared a story about a local entrepreneur who ran a bus service for Soldiers to visit the bustling red light district across the border. During Prohibition, visitors parked their vehicles on the Arizona side to cross over to Mexico.

Naco has earned an interesting historical footnote for being the first aerial bombardment of the continental United States by a foreign power.

The incident took place in during the Escobar Rebellion in 1929. Rebel forces battling Mexican Federales for control of Naco, Sonora hired mercenary pilot Patrick Murphy to bombard government forces with improvised explosives dropped from his biplane. Miscalculating the locations of his targets, Murphy mistakenly dropped suitcase bombs on the American side of the international border on three occasions. This caused quite a bit of damage to private and government-owned property, as well as slight injuries to some American spectators watching the battle from across the border. A depiction of Murphy in his biplane adorns the wall of the Gay 90s bar commemorating the bombing.

When hostilities waned in the region, the Naco Hotel advertised its rooms as “bulletproof.”

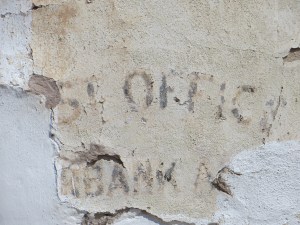

The remnants of the Naco Hotel still stand. Once advertised as safe from violence on the Mexican side of the border, locals still refer to it as the Bulletproof Hotel.

Ghosts of boarded up buildings along a once busy street hint at a vibrant borderland. I look forward to coming back to the Gay 90s Bar for a thirst quencher and to learn more about the time Nancy Reagan visited and got a bit tipsy. Maybe with some liquid courage I’ll walk through the port of entry to eat a meal in Mexico.

I live in a place where everything the light touches is the border. It isn’t some distant, ominous presence making headlines. It’s a place populated with resilient people withstanding the winds of change and it’s much closer than I realized.

Faded signs on abandoned buildings line a formerly thriving thoroughfare.